The Adoption of “Legge Pica” Legislation August 1863

By: Tom Frascella April 2017

Background

Most people are unfamiliar with the term Legge Pica. For that reason a brief background regarding this legislation is in order. A significant percentage of the southern Italian population initially supported Garibaldi’s 1860 campaign to oust the Bourbon regime from control of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. However, as is the case in most “civil” conflicts, support was not universal and opinion regarding unification of southern Italy with the Piedmont-Sardinia monarchy was also not universal. So “political” opposition to unification with Piedmont did exist even during the initial phases of Garibaldi’s campaign. These political conflicts resulted in a number of minor incidents of civil unrest and objection to Garibaldi’s “provisional” authority in the Sicilian territory as it came under his control. The incidents started early, even before Garibaldi’s Sicilian campaign concluded and he crossed onto the southern mainland. These incidents, while relatively few, were dealt with by Garibaldi’s “volunteer” military harshly. Punishments ranged from imprisonment to execution. These first acts of suppression of opposition were taken against civilian populations on the authority of Garibaldi himself, acting as “liberator’ in the name of Piedmont King Victor Emanuel II.

In addition, to civilian political opposition to unification with Piedmont there was also the pro-Bourbon faction in the south of Italy that remained loyal to King Francis. In the waning days of Garibaldi’s mainland campaign, the fall of 1860, the Bourbon Monarch, King Francis, became isolated with his remaining loyal soldiers in northern Campania. In all of southern Italy, northern Campania’s civilian population appears to have been the most heavily pro-Bourbon region of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. This loyalty is probably the reason why the King retreated there as Garibaldi’s forces marched on Naples. It is also where, when King Victor Emmanuel II arrived to take charge, King Francis called for the civilian population of the Kingdom to rise up against what the Bourbon monarch whose approach he deemed an invasion. While there was little in the way of actual civilian response to King Francis call for civilian action, there were a few pockets of civilian support and revolt in northern Campania. King Victor Emanuel’s Piedmont military were equally harsh in putting down any resistance to his takeover.

After he arrived in the fall of 1860 Piedmont’s King Victor Emmanuel continued to meet any pro-Bourbon civilian support in northern Campania by sending in his regular army troops. Response from Piedmont was swift, merciless and often fatal to the inhabitants of the few municipalities that demonstrated support for the then still official King Francis. In a sense these early direct encouragements of the use of excessive force against the civilian population sent a clear signal that Piedmont would not tolerate insurrection and was more than capable and disposed to serious reprisal for what it perceived as disloyalty to the unified State.

After the collapse of the Bourbon regime and its exile to the Vatican States, the south officially declared itself to be “unified” by vote in the southern plebiscite in 1860 which in turn was ratified by Parliamentary affirmation in early 1861. While this may have officially concluded the matter of formal unification it obviously did not address the political fragments that still existed in the south.

As part of the Parliamentary procedure, unification was “said” under the terms of the ratification to have extended and bestowed the existing Constitution of Piedmont to the entire territory that had been the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. This extension of the Piedmont Constitution was to include the same civil liberty guarantees enjoyed by the people of Piedmont and northern Italy to the people of the south. On paper it appeared that the people of the south would be incorporated into a unified Italy as equal citizens. However, in practice as we have seen in previous articles, those liberties were almost immediately denied to the people of the south. In addition, instead of reaching out to heal the wounds of civil war in the south, programs were instituted to segregate and alienate perceived opposition to the Piedmont regime and to siphon off the wealth of the southern Kingdom.

Whether encouraged by fear of insurrection, disdain for the culture of the south, greed or power Piedmont seems to have regarded the southern population more as a conquered people than as fellow nationalists. At the same time very early on you begin to see the expression by northern politicians that southern Italians are not “really” even Italians. As early as 1860 a Piedmont envoy to southern Italy wrote to Piedmont Prime Minister Cavour stating, “What barbarism! Some Italy! This is Africa: the Bedouin are the flower of civil virtue compared to these peasants” Darkest Italy, page 35. Additionally former Garibaldi General Ninio Bixio assigned after unification to a parliamentary commission to study brigandage in the south wrote, “in short, this is a country that should be destroyed or at least depopulated and its inhabitants sent to Africa to get themselves civilized”. “Darkest Italy, page 35.

Inexplicably this Piedmont attitude of disdain for southerners included disdain for many of those same southerners who had supported and sacrificed for the goal of a united Italy. This was apparent when in 1861 Piedmont required all those “insurgents” who had been labelled briganti by King Francis but who had fought with Garibaldi in the south for the cause of unification to report for arrest.

Of course, as the promises of equality, democracy and civil liberty were denied the counter demand for social equity and justice spread, especially in the rural south. But these protests and demands were met with political and social oppression rather than understanding, cooperation or national fellowship. By the spring of 1862 civil unrest, caused by the systemic injustices being applied in the south began to result in protest riots and in some instances armed revolt against isolated local municipal authorities, especially in the rural provinces. It became evident to most rural southern Italians after unification that only those politicians supported or installed by Piedmont would be “elected” and therefore represented Piedmont’s interests rather than their true constituents.

Inevitably Piedmont’s response to any opposition resulted in the use of its military . Military excesses were actually officially encouraged rather than discouraged. The result was a number of massacres in which unarmed civilian populations, including men, women and children, suspected of sympathy to opponents of the Piedmont regime were brutally executed. Often the commanding officers and units were decorated for their heroic actions slaughtering unarmed civilians. The military attitude was as one officer put it later in 1868; “the commander here is a certain Milon…he is a resolute and decisive man, and he has already done a great deal of good for his area, but he has a great amount still to do. He must keep Dante’s maxim well in mind: “Here pity lives when it is altogether dead.” When there is a well-established knowledge that people have been helping the brigands, they are shot without pity and without a trial.” Darkest Italy, page 40.

The implementation of this attitude and action in turn resulted in the creation of a number of “bands” of people forced by oppression and injustices into insurrectionist armed revolt. Early in 1862 these bands were mostly independent and scattered throughout the south. It can be said however, that they were composed of roughly three elements of the southern Italian population. First, there were those, mostly in northern Campania, that were persecuted for their Pro-Bourbon loyalties many of whom were former Bourbon soldiers. Second, there were those who had become identified as “anti-Piedmont” by virtue of their opposition, on any issue, to the administration of Piedmont’s agenda in the south and its broken promises of equity and civil liberty. There also was a small but active group of non-political nonconformists many with criminal agendas or actual previous criminal histories.

While their numbers were originally small, the ever increasing heavy handed infliction of injustice, resulted in an ever increasing number of aggrieved persons some of whom then joined the conflict. The danger, which the Piedmont regime recognized was that the various factions although without a common ideology might form a united opposition. This threat was made all the more real by the exiled King Francis who continued to call for revolt and whose presence in nearby Rome offered at least the potential of the conflict being cast as a struggle for the return of the former King and dynasty. It also represented the threat that funding and arms might flow into the rural south whose population was basically unarmed and without the financial resources to arm itrself.

To this volatile mix of what was taking place in the south was added a new element in late spring early summer of 1862. Garibaldi’s and the “Young Italia” movement reappeared in Sicily and began a brief attempt to raise another “unifying” army to invade the Papal States from the south. While several thousand “volunteers” briefly took up arms with Garibaldi, no great volunteer “mass” army of unification materialized around his attempt and it failed very shortly after it was launched. The failure was in no small part due to Garibaldi’s insistence that his men not engage the Piedmont forces. Piedmont forces were dispatched to intercept Garibaldi as his actions did not have Piedmont approval. Roughly three thousand Garibaldi’s volunteers were captured and imprisoned. However, Garibaldi’s failed attempt lasted long enough for Piedmont to issue formal declarations of “emergency” martial law first in Sicily and then in rural southern Italy in response to Garibaldi’s new campaign.

The issuance of these “emergency declarations” of martial law where not authorized within the framework of the existing Italian Constitution and therefore, existed beyond the scope of authority of the government to issue. However, the edicts despite being “unconstitutional” were asserted by the Piedmont regime to be justified as necessary in the militarized state of emergency created by Garibaldi. In essence Piedmont’s position was that Garibaldi’s movement was “political” insurrection and a threat to the authority of the State. This threat “justified” in Piedmont’s argument the extraordinary declarations of martial law. Further, the imposition of martial law was declared as only a temporary measure and therefore not inconsistent with the constitution as the first responsibility of the State was self-preservation..

As the impetus for creating the edict of martial law was supposedly Garibaldi’s second campaign which folded almost immediately one would think that the “temporary” edict would dissolve with the capture of Garibaldi and his forces. But the Piedmont military in the south found martial law too useful a tool in its struggle against the ragtag insurgency in the rural south to abandon its use. So, in effect the Piedmont forces in the south were able to transfer and apply martial law to the civilian population of rural southern Italy in their effort to quell civil unrest despite there never being any major threat to the regime. In written correspondence between General La Marmora and Prime Minster Ricasoli in 1861 and 1862 you catch glimpses of their thoughts that the south can only be governed by harsh demonstration of power; “One must give example of a strong Government and impartial administration to the southern peoples…You recognize the nature of the southern peoples and know how little it takes to win their affection. One must satisfy their imagination and, at the same time, their expansive character”. Darkest Italy, page 41.

But as the military based atrocities, massacres, arrests, rapes, executions without trial, and mass imprisonments based on alleged complicity mounted, the deplorable deterioration of civil rights of the people of the rural south became difficult to hide from the European press. It became obvious to Piedmont and her allies that deflection in the eye of the European community from their oppressive acts was needed. A search for an appropriate “villain” a “constructed” culprit for the cause of the atrocities, other than the Piedmont army needed to be found.

Piedmont with the Aid of Its Allies casts the Pope and King Francis as the Devil

As we have already seen the spin favored by Piedmont and the Mazzinians was to cast the Pope and the Bourbon monarchy as the main causes of every ill in southern Italy. This take on the problems of the south can be found in the northern Italian and English press for almost two decades prior to Garibaldi’s campaign. This was primarily done in England in order to orchestrate public perception within the United Kingdom to support regime change in southern Italy. As it became more and more evident that Piedmont was at least as violent and aggressive against the people of the south as the Bourbons were, the complicity of the Bourbons and Pope became a convenient and already established deflection for Piedmont’s aggression. In 1861 and 1862 rebellion and civil unrest in southern Italy was cast as originating and promoted by the Bourbon’s with the aid of the Vatican. While some of the insurgents certainly had Bourbon connection, those other insurgents who rebelled against Piedmont aggression were ignored or lumped with the pro-Bourbon forces. The civilian victims of Piedmont’s aggressive suppression, the southern Italian people, were cast as victims of the Bourbons and the Pope not the Piedmont regime.

When as in the Parliamentary debates in Italy in early 1863 and in England in May opposing views of the true causes and perpetrators of the crimes against civilians were raised those voices were quickly silenced by the establishment. It is within the context of this governmental public spin that the Bourbon attempt to further its own goals of restoration played into the Piedmont and English narrative. As I wrote several article past, King Francis dispatched four loyalist lead by the La Gala brothers to France to recruit Spanish insurgents loyal to the Spanish Bourbon cause to his Italian cause.

The role of Napoleon III as a secret supporter of the Piedmont unification cause was not well appreciated by either King Francis or the Pope. The fact that France had given sanctuary to Spanish insurgents loyal to the Spanish Bourbon Monarchy and was “protecting“ Rome made it appear Napoleon was an ally of the Papal States. It also made it appear that France would therefore be supportive of the La Gala mission to France. Nothing could be further from the truth. By the time the La Gala party was “secretly”, with false identity papers, smuggled on to a French ship from Rome, the French had already alerted the Piedmont regime to La Gala’s mission. Although the French ship was destined for a French port it was also scheduled for a stopover in northern Italy. This meant that the ship would briefly be within Piedmont territory.

So in July 1863 four men, passengers aboard a French ship supplied with false identities found themselves in the port of Genoa. As they had no plan of disembarking on Italian territory this would normally present no opportunity for discovery by Italian authorities. Their false identities and actual identities would not be subject to Italian scrutiny. However what occurred makes it clear that the French alerted the Italian authorities to the presence and true identities of the passengers. The Italian authorities at the port, asked the French consul in the city to allow the Italian authorities to board the French vessel in port. This is highly unusual as the ship, its cargo and passengers are by international law while on board in French territory. Further, no secret was made by the Italian authorities that the purpose of the boarding was to arrest the four men whose real identities were already known to them. The act of arresting passengers on a “French ship/ territory:” and then removing them to Italian territory for imprisonment is actually an illegal act. The boarding and arrest actually was a violation of international maritime law which cannot be superseded by acquiescence of the French consul. He had no such authority.

Also as we have previously described the men were originally arrested under Italian warrant for the “crime” that they were yet to commit, that crime being support and recruitment in the cause of restoration of the exiled Bourbon King. This was initially thought to be a “great” public relations coup for the Italian and English governments as it “proved” their narrative that southern Italian “insurgents”, these specific men, were from northern Campania and agents of the Bourbons. These men as loyalists were working with the Bourbon King and the Pope to “undermine the Piedmont regime just as the Government had said. However, as this narrative developed these men were repeatedly described as engaged in “political” actions against Piedmont and unification. That would seem to be alright as that is what the Piedmont and English governments wanted to project. It was in fact alright only until they discovered that there was a twenty year old treaty between France and Piedmont which did not allow for the extradition of people accused of “political” crimes. So the transfer of the La Gala group was not only a violation of international maritime law but also the exchange or delivery of “political” agents was forbidden between Italy and France by specific national treaty.

So the narrative of the capture had to change in mid-propaganda in order for the arrest to be internationally “legal. These originally defined and declared “political” prisoners, agents of the Pope and the Bourbon King had to be transformed into common criminals and murderers supported by the Bourbon King and the Pope to avoid the consequences of the treaty between France and Italy. Only in this way could the Italian and French governments claim that they were not extraditing “political” prisoners. This of course was a complete farce. However both Piedmont and France felt it was a necessarya necessary “international” farce.

For purposes of the “new” public spin the insurgents were arrested not for being engaged in political rebellion but rather for being common brigands/murderers and thieves. However, this maneuver also had its drawbacks. The fact that Piedmont had for over a year been imposing martial law because of political rebellion rather than criminal law because of banditry made their military acts against the civilian population no longer a legitimate assertion of authority. Criminal civil law should apply to banditry under the Piedmont Constitution. As a result of this legal quandary, the Italian Parliament in Turin began to consider civil legislation basically mirroring the harshest of the martial law edicts the military commanders had been dealing out in rural Italy. However it was reasoned by packaging the actions of the military as following this newly created “civil” litigation they could claim it was not martial law. Those that had been “insurgents” were re-labelled common brigands for the same offenses that they had been labelled insurgents. This new legislation would become known as Legge Pica or the Pica Law. The sad reality for the people of southern Italy was that by thus changing the law and the labels it became necessary to label literally the entire rural population of southern Italy as “brigands, suspected brigands or potential brigands in order to effectively enforce the goals and outcomes the martial law was meant to dictate.

The Pica Law

As stated it should be appreciated that since Piedmont’s actions were under some international scrutiny the broad brush of martial law offenses now encompassed by civil legislation were hard to apply to a whole region of the country under the guise of brigandage. The region was now not one of civil unrest but widespread criminality. The narrative developed to accompany this new law was that this new law was establishing “order” and “cultural” change on a the southern rural people for their own good because they were “inherently” criminal. Piedmont created the argument that they were abolishing civil rights for a third of the citizens of Italy because they were all criminals who needed external civilized control. To be clear the Pica law was created and implemented only against the citizens of rural southern Italy and therefore Piedmont had to argue that only that part of the population was culturally and inherently criminal. In essence the creation of this law and its implementation required a narrative that separated the country and its people into two distinct moral groups. The moral “northern” Italian and the immoral “southern” peasant Italian. As we will see, not far behind this narrative of two distinct moral groups would be the development of an Italy with two distinct racial groups, north and south as well.

As the author of Darkest Italy, John Dickie, puts forth the explanation for the logic and administration of the legislation on page 39:

“The further brigandage could be located outside the judicial space, the easier it was to legitimate the exceptional legislation formed to suppress it. Indeed, if brigandage was constructed as the very antithesis of law, civilization, and reason, then the use of unconstitutional measures to combat it becomes not only justifiable but ethically imperative. The political effects of this type of representation of brigandage is evident from an article which appeared during the summer of 1863 in Il Pungolo… It asserts that “everyone” is convinced of the abhorrent nature of the phenomenon, but condemns those who do not have the burning desire to combat it with “decidedly extraordinary means’. Representing brigandage as the worst nightmare of a hypostatized law or society makes it the pivotal point of legitimate political dialogue. Its demonization creates and polices a consensual boundary beyond which one may not go without becoming guilty-a bandit by association. The more enthusiastically one abominates the enemy, pushing further the Manichaean logic of anti-brigandage, the closer one is felt to be to the center of the differentially constituted social space.”

You can trace the widespread perception that southern Italians are “all” criminals. Mafia types, to this legislation and the rhetoric that had to be orchestrated to support it. To further cover the evil and disparaging nature of this legislation, they cleverly had it introduced by a Piedmont supported southern politician by the name of Giuseppe Pica.

The legislation was proposed in the summer of 1863 and became the law applying to southern Italy and Sicily, only, in August 1863. Brigandage became punishable as an offense under the following terms; “According to the article proposed by the Parliamentary Commission of the Inquiry into Brigandage, since the words “attack” and “resistance” are not in it, the brigand would be shot for resistance alone, even if he had not yet committed any crimes. If he had committed a misdemeanor he would be shot, and if he had committed a crime he would be shot, shooting would be the punishment for the crime of brigand, and not for his misdeeds according to their severity.” Darkest Italy, page 42. So simply being accused of being a brigand was sufficient cause to be shot. Guilt by mere affixation by an authority of the label brigand was all that needed to bedone.

What were some of the actions that could be construed as brigandage under the Pica law, according to a letter from the advocate General in Turin in late 1863, he defined brigandage as; “The crime of brigandage… is a continuous crime with an indeterminate character inclusive of all those crimes and misdemeanors which are committed by those who go around the countryside in groups of three with this objective in mind”. Darkest Italy, page 42 & 43.

To better understand the harsh and suppressive nature of this legislation and how it affected the culture and function of rural southern Italian society we should examine some of its main elements. In reviewing these features of the law one must remember that the rationale for the law is that literally all or most of the people of the rural south are “criminals” by virtue of birth. So in the south under this law;

1. Any individual caught in rural southern Italy “armed” would be “arrested” by the authorities and shot either with or without trial. The term armed came to be interpreted in the loosest of meanings, armed with any kind of gun, pistol, musket or rifle including guns used for hunting birds or game. It also came to include knives including knives commonly used in agriculture.

Piedmont firing squad shooting southern Italian brigands.

Since all southern Italians under the law were potential criminals, all caught with any kind of weapon were prejudged criminals engaged in criminal activity, brigands. Therefore they were subject to summary execution. It made no difference that poor southern Italians farmers needed weapons and knives in pursuit of their farming activity. It also made no difference that rural farmers in the south traditionally supplemented their normal diets with game from the woodlands of the region. So the law created a choice for rural southern farmers of execution for disobeying the law or slow starvation for the farmer and his dependents. Since there was no trial there was no defense to the labelling of individuals as brigands.

Execution by firing squad had since the inception of the insurgency been the preferred way of administering “justice” to southern Italian insurgents. As stated in Darkest Italy, page 44, “During the civil war, execution by firing squad became the emblematic method of dealing with brigands.: the thuggish General Pinelli announced that it was the penalty for insulting the House of Savoy, the King’s picture or the Italian flag. Vast numbers of peasants seem to have met their end this way. For the protagonists of the repression, in a situation where the local judicial apparatus was seen to be either in chaos or in cahoots with the reactionaries, the firing-squad was viewed as an efficient, portable, and quick means of meting out justice, a laconic contrast to the long-winded civilian legal process”.

In line with this criminality claim Piedmont’s Legge Pica also declared that;

2. Towns and villages that were deemed by the authorities as “hostile” to the Piedmont government were now under this new civil Pica Law allowed to legally be sacked looted and burned to the ground.

Of course, the reasoning goes, if a town was little more than a nest of criminals and thieves then why should it exist. The extermination of these towns and its inhabitants would in fact bestow a benefit on proper society. Any property within the town could be considered ill-gotten gains and therefore undeserved by the inhabitants. So it could now be looted by the northern soldiers as a just reward for enforcing the highest standards of Italian culture against the morally inferior southern peasants. As indicated in an earlier quote, depopulation of the region was a legitimate goal.

Since everyone is a criminal/brigand the law addressed how they should be dealt with;

3. Anyone “suspected of being a brigand, sympathetic to the brigandage cause, or a relative of a brigand or suspected brigand could be arrested, imprisoned without trial, formal complaint or indictment. Eventually, this included the arrest of the oldest daughter of a suspected brigand who by the nature of being a brigand’s daughter was subject to a sentence of up to 16 years in prison.

Clearly if you are guilty by presumption and birth, it is hereditary. No need for trial or proof. Arresting daughters is a sure way to make sure the genetic criminality is not passed on.

Further lumped into the “criminal” conspiracy was;

4. The law subjected to arrest, imprisonment or execution anyone considered an accomplice to the brigands. Among those behaviors that were considered supporting brigandage were; individuals that had ownership of weapons without a government license, individuals caught “working” in the fields without a pass, in other words caught beyond the town or village bounds without permission, also any individual that carried more food beyond the village confines than was sufficient for one meal, kept too large a store of food in one’s house, shod horses without a permit or kept or carried horse shoes.

This portion of the law aimed to restrict the movement of people in and around their villages. It makes sense that natural brigands need to be restricted in their movements and their lives need to be regulated less they freely engage in any activity which will always be criminal. The law also allowed for imprisonment, which served as a way of separating people from their community as a punishment for relatively minor offenses. It was believed that the threat of separation even more than the imprisonment had a psychological impact on the southern Italian resolve. “The effectiveness of this punishment was commended to us by almost all the honourable magistrates and jurists we interviewed. They all made us reflect on the fact that, in addition to this punishment’s intrinsic effectiveness, there is also the advantage that derives in this special case from the nature of the southerners, who are extremely fond of their own land, infatuated with their own sky, and unbelievably averse to the thought of leaving the house where they were born. Even just the announcement of this new punishment would bring about a salutary and useful fear.” Darkest Italy, page 41 & 42.

Another aspect of the law which sought to restrict the movements of the population;

5. The military was also authorized to destroy any huts found in wooded areas, walling up or destroying outlying buildings to reduce line of sight approaches to population centers, and requiring people and cattle, sheep and goats to be collected and confined to central areas were they could be under the guard and watch of the military and police authorities.

Of course there were the two general authoritarian provisions that regularly show up when suppression on this scale are imposed;

6. The press could not criticize the government or publishers and reporters risked arrest and imprisonment. Rigid enforced censorship was implemented.

Followed by the always popular;

7. Citizens could not express either opposition to or neutrality to the Piedmont regime.

In implementing these strict measures the civilized northern troops gave great thought to the manner in which atrocity should be committed. Even the “proper” orchestration of summary execution of brigands had a rationale as shown in one example. This involved the execution of two brigands named Pinnolo and Bellusci which was to be conducted in front of a large crowd. According to the newspaper account;“Pinnolo and Bellusci were not walking, but running, and the priests in attendance were struggling to keep up…Bellusci looked at the Church and said to the priest, “Father I would like to be shot near the walls of hat Church.” “That can’t be done.” “But at least they could let me kneel first.” “Its not up to me.” “Then commend me to God.” These were his last words. Twelve rifles fired at Pinnolo and Bellusci’s back..” darkest Italy, page 45.

Another interesting aspect of the proper protocol for executing brigands was that they should be shot in the back as a sign of their betrayal to the State. When executions did not go as planned there could be ramifications for the officers in charge. As described in Darkest Italy, pages 46 and 47; “Another individual incident gives some idea of the conflicting arguments even involved in the execution of a male brigand. In May 1865 near Potenza, Vito Francolino, condemned to be shot in the back, seems to have broken the rules of decorum attached to the firing squad. On hearing the order to fire, he ducked and, although wounded, made off across the countryside pursued by the firing party who sustained a number of injuries before the fugitive was captured and bayoneted on the spot… The case drew the attention of the minister of war, concerned about the conduct of the Captain Bertagni, who had been in charge of the execution. “

The war ministry in reviewing the affair criticized the Captain in the following note to his record; “much more than for the failure to take the necessary precautions, Captain Bertagni should be called to account for the subsequent inhuman killing of the fugitive. This episode which dishonors the army, and for which there is no corresponding sanction in the Code… The brigand Francolino had been condemned to be shot and not to be barbarically slaughtered with sabre and bayonet blows…”

So clearly there was a right and wrong way to summarily execute people.

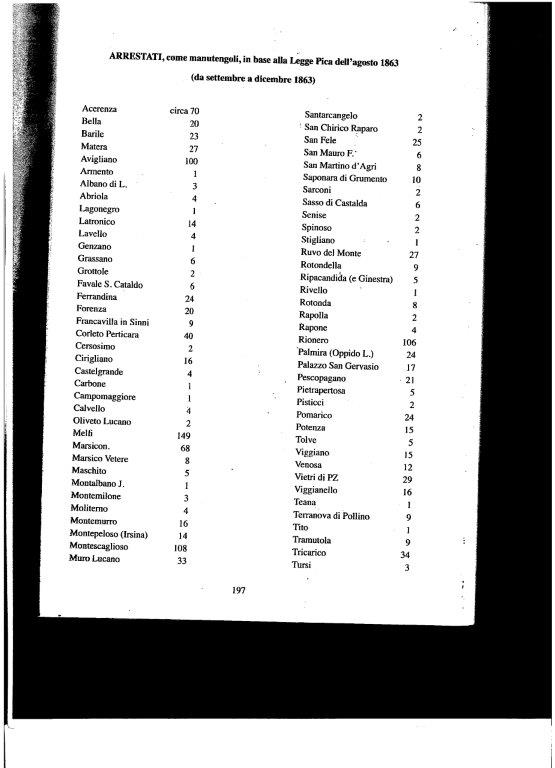

As an example of how the Legge Pica impacted the people of the Lucania region, in just the first four months after its passage in August 1863 the following is list of the numbers arrested. The count is taken from the book “Brigantaggio Lucano Dell’Ottocento’ Il Dizionario” page 197. Of note, 25 individuals were arrested from San Fele alone in those first four months, a town of 10,000. Also, 20 from the neighboring town of Bella where the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anton Scalia mother’s family was from and 17 from San Gervasio where I understand Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s mother’s family was from.

list of the numbers arrested

As Italian- Americans it is I think important to understand that labelling of rural southern Italians as criminals served a specific political purpose and has lingering negative impacts on both present southern Italians and the descendants of those who left southern Italy over more than a century and a half as part of an intentional forced depopulation of the region.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey