Early U.S. Catholics and Catholic Immigrants 1790-1850

By: Tom Frascella MARCH 2014

The story of Catholics and Catholic immigration/ assimilation into the U.S. population is story of continuous growth. The stories of the Sartori and Hargous families are an important part of the early chapters of that story. However, having written about these families it is appropriate to also give a brief overview of what was the perception and statistics relating to U.S. Catholicism was nationally from the earliest days of the Republic.

Catholics represented a very small minority in the original U.S. population as determined by the 1790 census. Out of a U.S. population of four million people, Catholics numbered only 35,000 or roughly 1%.

Over the next thirty years the U.S. grew in territorial size and in population, reaching a population of ten million by 1820. Of those ten million roughly 2% were estimated to be Catholics or 200,000. So in the first thirty years of nationhood the U.S. Catholic population grew five fold and doubled in percentage of the total U.S. population. This was significant growth but continued to demonstrate that Catholic presence was a relatively minor factor in the overall demographics of the country.

It should be noted that not all of the growth during this first thirty year period was from direct immigration. As we have seen in the example of the Hargous family some of the increase did come in the traditional sense, from exiles fleeing from France’s various political shifts as well as from other traditionally Catholic European countries. But many in the growing U.S. Catholic presence represented native born individuals whose families were colonists in formerly French or Spanish territories. Some of these previously non English colonies had by 1820 become annexed to the U.S. Despite this rapid growth in the number of Catholics the vast majority of the U.S. population continued to be rooted in an Anglo-Protestant heritage.

U.S. social dynamics however, began to change as a result of a surge of mass immigration to the U.S. starting around 1830. This type of immigration was new to the U.S. both in sheer numbers and point of origin. With the end of the Napoleonic era around 1830 and the continuing northern European crop failures of the time, large numbers of non-English Europeans began to seek a new life in the Americas. This was the U.S.’s first experience with massive waves of culturally diverse. These immigrants began arriving primarily from Germany and Ireland. Southern Germans and the Irish were predominantly Roman Catholic in their traditional religious practice.

The U.S. was ill equipped to cope as a society with tens of thousands of newly arrived people many of whom were poor and without resident family or friend support. In addition, many of the newly arrived did not speak English and the Country’s educational and social institutions were poorly equipped to provide opportunities for smooth transition into an English speaking U.S. mainstream. Adding to these problems were long standing European/old world historic problems, political, social, ethnic and religious especially between the Irish and the majority mainstream American Protestants

The impact U.S population statics of tens of thousands arriving is demonstrated in the census of 1840. By 1840 the U.S. population had grown to approximately seventeen million people with 600,000 Catholics or 3.5% of the total population. What this demonstrates is that in a twenty year period, or the equivalent of one generation, the U.S. population increased by 70% while the Catholic population increased by 300%. As the Catholic presence grew so did the ancient prejudices and inter-Christian friction that had existed for hundreds of years in Britain. These prejudices manifested in many ways, particularly against the Irish, and it was not long before U.S. political debate began to reflect those rising concerns.

By the late 1830’s the growing anti immigrant political pressure began to build significantly. Generally, this pressure and the individuals who supported the anti- immigrant position were labeled “Nativists”. Candidates for political office began to adopt Nativist positions in their campaigns and it proved to aid in their electability.

The U.S. Nativist movement intensified as the Irish “potato famine” and British anti Irish home policy intensified throughout the 1840’s. British home policies caused more and more Irish to immigrate. By the 1850 census with the intensified Irish immigration, the U.S. population was recorded at twenty-three million, a gain of six million in a single decade, or 35%. With regard to the Catholic portion of the statistic, U.S. Catholics numbered 1.6 million, a 270% increase or 7% of the total U.S. population. Catholicism was on the verge of becoming the largest Christian denomination in the U.S. for the first time in the country’s history.

With this as statistical/political backdrop we can look at what was going on in Trenton’s Catholic/immigrant community as well as the New York and Philadelphia communities from 1830-1850’s. I include Philadelphia and New York as these two cities served as the Diocesan administrative centers for New Jersey’s Catholics up until 1851 when the Diocese of New Jersey was originally established.

Trenton escaped much of the 1830-1850 anti-Catholic/ anti-immigrant hysteria of the time only because Trenton saw little general population growth. While Trenton’s Catholic/immigrant population grew it did not do so dramatically from 1800-1850 as to seriously effect Trenton’s ethnic balance. In the U.S. census of 1800 Trenton’s population was recorded as 5,000 and in 1850 it had grown to only to 6,000. So while the country’s population during those fifty years went from 4 million to 23 million Trenton’s population only grew from 5,000 to 6,000. The stability and lack of growth kept the local Trenton anti newcomer sentiment to a minimum. However, in the more rapidly growing northern part of the State as well as the large east coast port cities where immigrants were landing and taking up residence a different story was unfolding.

In the 1830’s America’s second largest national party the “Whig” party began to unravel with internal dissent on many political issues chief among them abolition, prohibition and immigration. By the late 1830’s the collapse of the Whig Party gave rise to a number of small parties as potential replacements including the anti-immigration party known as the American Nativist Party. By the mid 1840’s the Nativists had a substantial and aggressive political following and had garnered a number of National, State and local political offices. The American Nativist Party had also closely allied itself with the American Protestant Association. Together, at least in some venues including Philadelphia and New York, the combination proved initially very politically effective.

The American Nativist Party political platform was built around a number of planks chief among them:

Party members in furtherance of their agenda were not beyond methods of intimidation and violence toward immigrants especially Irish immigrants and those others deemed sympathetic to immigrants. On May 3 rd of 1844 in Philadelphia matters reached a highly charged atmosphere. Several hundred Nativists in Philadelphia purposely entered the predominantly Irish section of the Third Ward of Kensington and set up a demonstration platform inviting Nativist and allied American Protestant Association speakers to rail against the Irish. A local Irish crowd jeered and tore down the grandstand platform and the Nativists supporters retreated. Among the themes espoused by the Nativist and Protestant speakers on that day were:

On May 6th the Nativists returned some three thousand strong to Kensington. Recognizing the potential for violent clashes at the behest of the local Catholic parish priests and Philadelphia’s Bishop Kenrick the local Irish community was asked to stay away from the demonstration and avoid confrontation. However the Nativist demonstrators moved their site into the active largely Irish “Nanny Goat Market” place and direct provocations turned into fighting. Many people were injured on both sides and two Nativists were fatally wounded. Two more Nativists were killed when they attacked the local Catholic Church building.

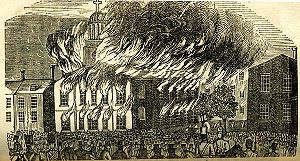

Bishop Kenrick of Philadelphia again tried to diffuse the situation closing the Catholic Churches to Sunday service and imploring non violence among the Catholic community. However, this only emboldened the Nativists and a series of assaults by rioters against Irish Catholics flared up in various parts of the City. The assaults turned into full fledged riots and the local unarmed police were unable to deal with the mobs. By the time order was restored six weeks later hundreds of Irish had been injured. The armed State militia had to be called in. The Nativist crowds were not easily quelled. Over twenty militiamen were killed, and dozens more Nativist rioters killed or injured. Many Catholic homes and businesses were also set ablaze by the rioters. In addition, two Catholic Churches were burned down, St. Michael’s, and St. Augustine’s. St. Philip Neri’s was looted and badly damaged. St. Charles Seminary and St. Augustine’s seminary were also burned down. St. Augustine’s had been the original Catholic Church in Philadelphia and was the missionary parish for the Trenton Catholic community before St. John’s Church was erected in 1814. Of note, with the burning of Olde St. Augustine Church and seminary one of the finest library collections in the U.S. was destroyed. Also almost lost was the “sister” Bell to the Liberty Bell which had resided in St. Augustine’s bell tower since 1790. Order was not fully restored in Philadelphia until troops of the Pennsylvania guard arrived in force, imposed martial law and demonstrated a will to fire on the rioters. In all some $150,000 in 1840’s dollars worth of property damage was sustained by Catholic owned Churches and businesses and around a hundred people lost their lives. In the arrests and trial aftermath of the riots none of the Nativist rioters were convicted of any wrong doing although a number of Irish were arrested and convicted.

Drawing from July 7, 1844 Philadelphia riot

Drawing of the Olde St. Augustine Fire

Observing their “success” in Philadelphia the Nativists in New York began to agitate in similar fashion. Like Philadelphia the mayor of New York City was a member/sympathizer of the Nativist Party. The Bishop of New York John Hughes had seen how well a passive Catholic approach had worked in Philadelphia and met privately with the Mayor. It is said that he assured the Mayor that if a single Catholic Church was burned in New York City, New York would become a wasteland. The mayor must have been impressed by the discussion as order was kept, and no Catholic Churches were burned. History records that Bishop Hughes earned the nick name “Dagger John” after his conference with the Mayor. The Mayor made it clear that New York’s professional and armed police force would not tolerate the type of lawlessness experienced in Philadelphia by either side. Philadelphia learned as well from the New York experience and the 1844 riots lead to the consolidation of the City’s various sections and the formation of an armed unified City professional police force.

Prejudice, discrimination and injustice continued to be vented upon the immigrant Catholics, especially the Irish in the succeeding decades. The movie “Gangs of New York” is a fictionalized version of the confrontations which were common well into the 1860’s and 70’s. However, the business and civic authorities were so fearful of the potential destruction and chaos that the Nativist activism could insight that the riots of 1844 helped reduce political support for the Nativists’ Party in the late1840’s and early 1850’s. Eventually began to fall apart for a number of reason, immigrant populations continued to grow, local businesses did not support the tactics, and the party split of the abolition issue. Anti- immigrant political pressure however has never disappeared. It reformulates as it did in the 1850’s under different political party name the “Know Nothings”.

With regard to Italian immigrants of the period unfortunately very little is written. It is likely that the same intense prejudices did not focus. In part this is because it is estimated that only about 10,000 Italians immigrated to the U.S. between 1790 and 1850 with about half returning to Italy. With numbers that insignificant it is unlikely that the average American of the period had ever seen or interacted with an Italian. It is difficult to focus much attention on a population that small and difficult to detect. It also should be noted that many Italian immigrants of the period from 1790-1850 were Carbonari, political refugees. As such they were either middle class or professionally educated upper class. Many were highly respected in their training and skills. This further allowed them to be somewhat insulated from the street/mob and ghetto political experience. As we shall see this social distance did not remain fact for long. Later as poor Italian Catholics began arriving in numbers they became easy to identify. They would take their turn labeled as “Roman” Papists of the most sinister kind.

© San Felese Society of New Jersey